[This post was drafted last summer but only completed and uploaded to the website in January 2019.]

Last year, TII published the National Roads Network Indicators 2017 which is their annual report on the state of Irish national roads. This includes national primary roads, national secondary roads and motorways although the report also includes some data on regional and local roads.

Following the same format as last year, the report is divided into the five sections, four of which are considered below:

- Road Network – presenting key statistics on the components of the road network

- Safety – looks at the number of fatalities in the network and whether the network is getting safer or not

- Accessibility and Environment – impact of investment on employment accessibility

- Economic – looks at overall travel demand.

Road Network

One of the interesting facts thrown up in the report is that 88% of roads deliver the highest level of Service A ie free flow conditions with 96-97% of roads delivering Level of Service C which is minimum stable flow.

The comparison with the Level of Service for cycle facilities is striking. Most cycle facilities offer the lowest level of service ie D. These include most of the greenways developed even those which have been hyped and spun as world class. They also include many schemes in urban areas where the allocation of space is the minimum for cycling but above minimum for motorised traffic. Local authorities consider such schemes to be in accordance with DMURS despite the hierarchy of road users prioritising cyclists above car drivers.

As in 2016, 39% of trips were estimated to be less than 15 minutes in duration and 38% of trips were less than 10km in length. There was also no change in the average trip distance at 19.4km and average trip duration at 22 minutes. Once more it shows the potential to substitute trips by bicycle if the government was to properly #Allocate4Cycling by providing adequate funding and specifying high standards.

The annual growth rate in traffic on the network was 3.0% nationally in 2017 compared to 4.6% in 2016. In the mid-east which includes Kildare and the other commuter counties surrounding Dublin the growth rate was 4.4% in 2017 and 5.2% in 2016. If maintained at this rate, the growth in traffic on national roads between 2016 and 2025 will be almost 50%.

SAFETY

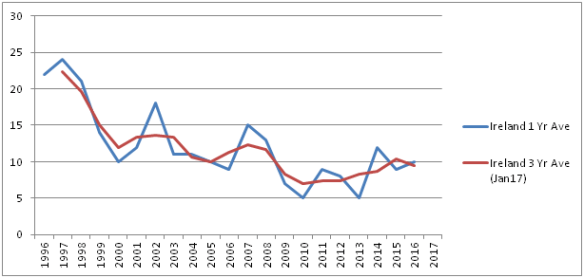

In the section of safety, TII pulled two sleights of hand in their presentation of road fatality statistics.

The 2017 Report gives a reduction of 28% between 2013 and 2017 (64 to 46 fatal collisions) but this disguises the fact that there had been a significant increase (72) in the number of fatal collisions in 2016 which the report ignores.

The three year average of fatal collisions on national roads is as follows:

| Year | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||

| Fatal Collisions on National Roads | 64 | 66 | 61 | 72 | 46 | ||

| 3 Year Average of Fatal Collisions on National Roads | 65.0* | 63.7 | 66.3 | 59.7 | 59.0* | ||

Table 1 Three Year Average of Road Fatalities on National Roads

* These are averaged over 2 years only as the third year is not available

The percentage difference between 2013 and 2017 is only of the order of 8% which is very different from the 28% reported.

The second sleight of hand is in relation to the different reporting periods. The 2016 report considered six years (2011-2016) whereas the 2017 report considered five (2013-2017). If they had used a period of 5 years in 2016 as in 2017, the change in fatalities would be from 48 (2012) to 72 (2016) – an increase of 50% which would take the gloss off the TII performance.

ACCESSIBILITY & ENVIRONMENT

The 2016 report states that a key benefit of a quality road system is improved accessibility to jobs which is generally seen as positive. The Impact of Road Investment on Job Accessibility between 2013 and 2017 shows this in graphical form. In practice however, this is seen in induced demand – longer commutes, more congestion in the urban areas and more noise and air pollution for those living in city centres and urban areas which are negative consequences.

ECONOMIC

The philosophy of TII in relation to traffic growth ( and by extension to climate change) is clearly set out in this section. The report states

Trends in overall employment in the economy drive commuting traffic whilst personal incomes are the major determinant of non-commuting traffic. With regard to the carriage of goods, economic output is the major determinant.

These statements are half right but simplistic. The underlying assumption is that the growth in commuting (motorised) traffic on national roads will be by private car. In the absence of any change in funding by the Department of Transport from roads to active travel, it excludes the possibility that there will be major increases in the number of people using sustainable modes of transport such as walking, cycling and public transport as required by National Transport Authority’s Statement of Strategy 2018-2030 and Smarter Travel. It also ignores policies on climate change and the potential risk of paying millions of euros for failing to meet our international obligations to reduce carbon emissions.

In considering 2017 and beyond, the report states

Given ….. economic trends, the prospects are for continued significant growth in National Roads traffic overall and HGV traffic in particular.

As cyclist fatalities have increased with increasing traffic over the last eight years, this is hardly good news for cyclists.